In order to properly explain my degree of appreciation for the work of three writers whose words I encountered in near-unison a few weeks ago (Seth Godin, Sir Ken Robinson, and Peter Brown) I need to first acknowledge that, since context, as we know, is everything, it is worth explaining certain conditions of these serendipitous discoveries.

Context: the end of the day at the end of the week nearing the end of second semester, at a desk in room 114 in a comprehensive high school with the highest concentration of poverty in the district, in June in southern California in year four of what many predict may be a record-breaking stretch of drought; when all that relates to School hangs like the stench of overripe gym shorts in a locker, and everyone that understands this is weeks from being dismissed for summer (except for those of us who will be back the week after graduation, for summer school). It’s time for reinforcements. One is thirsty and hungry and water for the cooler has yet to be delivered, and lunch - in terms of actual food eaten - didn’t happen. It’s the time of year when the word School, uttered in a certain tone, tends to immediately be followed by a sneer and some colorful expletive. Even the most dedicated among us are prone to bouts of seasonal malaise.

It calls to mind certain moments in history, of embattled troops desperately in need of reinforcements, aid, and water. I regret to say that when I consider my own first experiences with these academic doldrums, that History often comes to mind. Although some of my favorite people in the world are or have been History teachers, there is no denying that for many students, prior perhaps to their first “real” history (emphasis on story) class in college, the subject is irrevocably tied to a deep sense of absurdity at much of what happens in school: the rote memorization of facts and names in time for the test, after which they are promptly forgotten or crowded out by a new set of equally decontextualized facts stored just in time for the next test.

The historical tableau I am referring to is a scene from the American Revolution, one of the few I can recall in detail that have any bearing on a class with History in the course title. It comes not from my flashcards or lecture notes but from a book merely recommended on the reading list of a syllabus years ago, Scott Liell’s 46 Pages, a taut and engrossing overview of the import of Paine’s Common Sense on the outcome of the Revolution. Reading it a few years ago afforded me an opportunity to visualize, in great detail, certain critical aspects of the Revolutionary War beyond Betsy Ross’s mythical sewing of the flag, John Stafford Smith’s inspired composition of “The Star Spangled Banner,” or Paul Revere’s and his legendary galloping horse.

The scene is as follows:

It’s January of 1776, eight months into the war. The dominant ideology, if you can call it that, is doubt. George Washington is having difficulty maintaining an army, and the numbers of his men have been halved since June. Those remaining are prone to “insubordination and a lack of attention to duty” and “his greatest concern was the unwillingness of his experienced troops to re-enlist after their terms had expired.” At the time that he acquires a copy of Thomas Paine’s slim pamphlet, even Washington himself, like most of his peers, has “yet to conclude that independence is necessarily desirable or possible.” The effect of Common Sense on Washington’s own vision and morale is such that it prompts him to immediately distribute copies to all of his troops. Its contents crystallize a vision grown murky. It offers hope and purpose. And there, in the cold winter of a dark season, purpose is found again. The right words, offered at the right time, in the right context, become the torch by which we can connect the best of what we might become to certain parts of ourselves in the process of becoming.

With this in mind, I want to tell you of the way that finding Seth Godin’s manifesto at the right time, and in synchronicity with other finds, has renewed one educator’s spirit and hope: for the values and possibilities of schools comprised of dedicated individuals to nurture and encourage the growth of dreams.

Godin offers Stop Stealing Dreams available for free online, for all interested parties to share (“Just don’t charge for it or change it,” he asks). His longtime followers know that everything he writes is worth reading, be these one of his self-published (via crowdsourcing) bestsellers or his daily blog. He is genuine and committed, and rather than pander to any audience, his writing captures the musings of his well-informed head as directed by his generous heart, with inspiring faith that the world will receive and reward the deliverance of certain qualities that so many of us have thirsted for: slow-coming substance and quality over cheap and immediate superficial excess.

Themes central to Godin’s manifesto will be familiar to anyone acquainted with Ken Robinson and others calling for dramatic paradigm shift in education to mirror that which has already occurred within global society (for those who aren’t, see: “How Schools Kill Creativity” and “Changing Education Paradigms”), but nevertheless presented freshly with in Godin’s characteristically sensible approach to challenging accepted norms and outdated models. Godin observes The Shift from industrial economy to “connection economy,” and reflects on the implications for learners.

First, he stresses the importance of creating desire among today’s would-be scholars. This - above any other role - is now, more than ever, the best (perhaps only) way that today’s schools can be of real service. The reason for this is that the old role, of providing access to information, has now been completely eclipsed by myriad internet sources, most of which serve as vastly superior content delivery methods over the traditional textbook and lecture. In describing this great shift, Godin observes:

"…school used to be a one-shot deal, your own, best chance to be exposed to what happened when and why. School was the place where the books lived and the experts were accessible.

A citizen who seeks the truth has far more opportunity to find it than ever before. But that takes skill and discernment and desire… the goal has to be creating a desire (even better, a need) to know what’s true, and giving people the tools to help them discern that truth from the fiction that so many would market to us. "

For those of us who recall the misery of having to memorize dates and facts, we must acknowledge that, once upon a time, there was some kernel of truth to the rant that every history teacher seemed to be able to deliver, which generally ran along the line of, “How are you going to be able to do anything if you don’t know this?” It may have been hyperbole; however, it bears repeating that “in the pre-connected world, hoarding information was smart.”

And yet, “in the connected world all of that scarcity is replaced by abundance… of information, networks, and connections.” Anyone can know anything and most of us suffer from “knowing” too much indiscriminately (see the work of Daniel J. Levitin on Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload). A new survival skill emerges: being able to distinguish what matters from what does not; what is useful from what isn’t, to decide what and how the “what” of anything is useful, and to follow this decision with a well-considered response to its natural extension, “To whom? And, how?”

Basically, what you know no longer matters because anyone can know anything. The ability to care and make connections, though, and to remind information-overloaded, world-weary people what it is that really matters: this is everything.

Thank you for this timely reminder, Seth Godin. One grows weary of seeing students who seem not to care. Of course, in observing this, it is necessary to stress “seem” as something that exists in the context of a system that has taught them well that caring is not the point. By pausing to consider that the primary role of today’s educator is create desire by offering opportunities to consider how and why and what to care about, and freedom to learn how caring can lead to knowledge and to action and - above all, connection, the true currency of the “connected world” - well, that’s something worth doing, even if the road to understanding how to do this well may be long and steep.

In the same day, I encounter Ken Robinson’s latest TED talk, “How to escape Education’s Death Valley.” What a boon. I thought I had seen them all.

In this talk, Robinson outlines three principles by which human life flourishes:

"The first is this, that human beings are naturally different and diverse.

…

The second principle that drives human life flourishing is curiosity. If you can light the spark of curiosity in a child, they will learn without any further assistance, very often. Children are natural learners. It's a real achievement to put that particular ability out, or to stifle it. Curiosity is the engine of achievement.

…

The third principle is this: that human life is inherently creative. It's why we all have different résumés. We create our lives, and we can recreate them as we go through them. It's the common currency of being a human being”

In his characteristic witty meandering, Robinson relays how he and his family moved to Los Angeles twelve years ago (“Truthfully,” he says, “we moved to Los Angeles thinking we were moving to America, but anyway -- It's a short plane ride from Los Angeles to America.”) Then, in his charmingly roundabout manner, he steers towards a potent analogy at the heart of his message on a shift he terms the “grassroots revolution” in education - which has everything to do with nourishing the stolen dreams of Godin’s manifesto, the ghosts of which are no doubt have something to do with the end of the year malaise that threatened earlier in the week, as it does predictably several times each year, to smother hope. One wants to celebrate success, and does, in the form of those who are going off to college and those who have just won scholarships; the students for whom a life’s trajectory has just become something upon which they may exercise some influence. But the dead eyes are always so haunting; there are always those that have learned too early, the irrelevance of all that schools were traditionally designed to do. They seem unreachable. Compound the effects of a broken system with the trauma of broken home and you can almost smell it, the snuffing out of dreams, like the lingering scent of candles recently blown out. Let me be clear. This is not their deficit; this is not their weakness. This is the response of fragile and delicate life, made for bounding and blossoming, to overflow and explode and ignite - exposed to unhealthy and smothering conditions. Only then does it limp where it would run, fade where it would shine, die where it might have filled the air around it with blinding colors and dizzying scents. In the face of what, on certain days in certain months, can appear as barren land bereft of life, every groundskeeper needs regular reminders of the dormant potential lying just beneath the salt-crusted surface of the over-weathered earth. What if it bloomed?

Enter Sir Ken Robinson and his Death Valley analogy.

Nothing grows there because it doesn't rain. Hence, Death Valley. In the winter of 2004, it rained in Death Valley. Seven inches of rain fell over a very short period. And in the spring of 2005, there was a phenomenon. The whole floor of Death Valley was carpeted in flowers for a while. What it proved is this: that Death Valley isn't dead. It's dormant. Right beneath the surface are these seeds of possibility waiting for the right conditions to come about, and with organic systems, if the conditions are right, life is inevitable. It happens all the time. You take an area, a school, a district, you change the conditions, give people a different sense of possibility, a different set of expectations, a broader range of opportunities, you cherish and value the relationships between teachers and learners, you offer people the discretion to be creative and to innovate in what they do, and schools that were once bereft spring to life.

Hours after I’ve been renewed by Robinson’s TED talk, a dear friend informs me that Sir Ken has just released a book. No one can remember what its called but a quick search (fueled, obviously, by desire to know) leads to Creative Schools: The Grassroots Revolution That’s Transforming Education. As of this post, I am still in the opening sections, but it is clear that where some of his previous works criticized The System so effectively that teachers in certain moods might easily become overwhelmed with the enormity of the odds against transformation, this latest volume is quick to remind that while vast change is needed at all levels, the greatest potential to effectively respond can be found among teachers, because education “doesn’t happen in the committee room of the legislatures or in the rhetoric of politicians. It’s what goes on between learners and teachers in actual schools.” As far as students are concerned, "teachers are the system."

Back to Godin here. Another potent observation, in line with the necessity of creating desire, involves the proper care and feeding of dreams - which, by their nature, "are evanescent" and prone to quick suffocation. He aptly observes how "when they're flickering, it’s not particularly difficult for a parent or a teacher or a gang of peers to snuff them out."

"Creating dreams," on the other hand, "is more difficult. They’re often related to where we grow up, who our parents are, and whether or not the right person enters our life.”

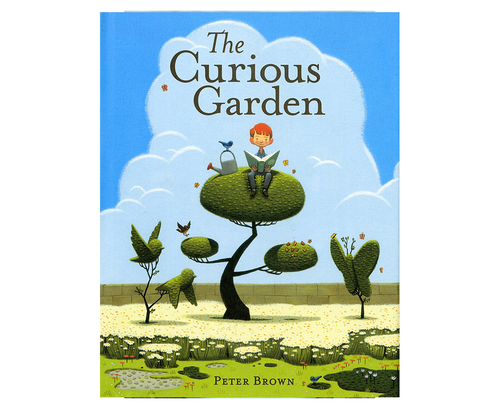

When I went to pick up Robinson’s book, at the end of the week in which I discovered and read Godin’s manifesto and watched Robinson’s talk, my five-year-old accompanied me as usual. Grace picks out her own books, following her own interests, and we generally leave with four or five apiece. On that day, one of her selections was Peter Brown’s The Curious Garden.

It is this last discovery that brings home the lessons of this week, reminding me why I love connections and discovery and learning; because, at its best, this is precisely what learning is: an organic blossoming of discoveries engendered by a constellation of experiences and discussions, both sought by and offered to, the active seeker. We need only to look.

The Curious Garden begins like this:

"There once was a city without gardens or trees or greenery of any kind. Most people spent their time indoors. As you can imagine, it was a very dreary place.”

When Liam, the protagonist, finds dying plants on the side of the railroad tracks he observes that “They needed a gardener,” and by the next page he understands that although he “may not have been a gardener, he knew he could help.”

"So he returned to the railway the very next day and got to work. The flowers nearly drowned and he had a few pruning problems, but the plants waited patiently while Liam found better ways of gardening."

At this point in the reading, Grace observes the goosebumps on my arm. “Look, mama!” I know, baby. Look indeed. Because they do wait patiently, even in a broken system. It's an innate human tendency, which we try sometimes to cover up by appearing to be hardened, even if each one of us knows that at any given moment in time, even the hardest-seeming shell is nothing but glass against the hammer of truth. We wait for reinforcements to come, and we’re prepared even on the brink of death and despair, to be nourished and reminded of our own capacities for tireless hope in our innate abilities as humans to believe our ways towards creating new realities, if only someone will remember well enough to share our own potential back unto ourselves at the right time.

Here’s to renewing faith in The Revolution. Here’s to the power of connections to ignite spirit. Here’s gratitude to those who offered the best of themselves and to the circumstances that somehow allow us, if we only know how to look, to find that which is was most needed at precisely the right time.

Here’s to renewing faith in The Revolution. Here’s to the power of connections to ignite spirit. Here’s gratitude to those who offered the best of themselves and to the circumstances that somehow allow us, if we only know how to look, to find that which is was most needed at precisely the right time. Finding these words in a children’s book at the end of the week, and connecting them willfully to others encountered days before, I am ready to stand up and go back in, fueled by belief in best of learning, the essence of which makes this space transcendent of spatial and temporal limitations, which is much greater than School in any form (sneer or no sneer), and which must - if we believe in it as we did when we answered the call to battle - be preserved at all costs, just as it must be protected, nurtured, and allowed to grow.

Return now to the vision of Liam, the curious gardener, observing how “the most surprising things that popped up were the new gardeners.” All around him, he saw others like him, inspired by the change he had catalyzed and the barren city was transformed.

Here it is: the hope that has been thirsted after like water in a drought, and nourishment in the days of no lunch, in the common sense wisdom of the hopeful keeper of the curious garden, and I have Seth Godin to thank for making connections and offering them for free, and Ken Robinson for recalling the dormant wisdom within each soul that has ever been called to education. Each, like the animated Liam, comes to it with some inchoate vision of change, and a water bucket.

Time for dusting off now, and preparing to begin again, with this vision in mind:

Many years later, the entire city had blossomed. But of all the new gardens, Liam’s favorite was where it all began.

Gratefully now, I bear witness to the power of a well timed manifesto, delivered in a time of need, to the right audience; to this capacity for awakening all that has been long-dormant to thriving abundance. One would rise immediately to arms except for the impulse to fall quickly to one's knees in awe at all the dormant dust of life emerging doggedly as ever was, or is, or will be, world without end.

...

Outstretched hand: chalk on cardboard provided by Sarah Joy on flickr under a Creative Commons license.

*The average human brain contains 100 billion neurons.

**When praised as a hero by a student in The Freedom Writers, Miep Gies, the woman who hid Anne Frank and others during the German occupation of WWII despite risking her life, gently refused to accept the title. Instead she offered this: we are all of us, no matter our station, called to be for one another, "a small light in a dark room."

...

Outstretched hand: chalk on cardboard provided by Sarah Joy on flickr under a Creative Commons license.

*The average human brain contains 100 billion neurons.

**When praised as a hero by a student in The Freedom Writers, Miep Gies, the woman who hid Anne Frank and others during the German occupation of WWII despite risking her life, gently refused to accept the title. Instead she offered this: we are all of us, no matter our station, called to be for one another, "a small light in a dark room."

We are social animals. Everything we have achieved as a species worth maintaining is born of the necessity of sustaining those relationships that lift us up from brutishness and command us to reach for perfection.

ReplyDeleteEducation is our instrument of inspiration. It should be more than information and the development of fundamental skills. Education should call young hearts to open, to understand and embrace subtlety, nuance and mystery. An education that lacks spiritual and social ritual is incomplete.

A real education is a journey from fear to understanding, from apathy to enchantment, from confusion to intelligence. In its highest manifestation, education teaches us to love– that one, the many and the universal.

Thank you Stacey Johnson for this powerful reflection on education and its role in stimulating creativity. A creativity directed at refining the human enterprise and an imagination that longs for that perfection that only love can realize should indeed be our goal.

Yes, let our schools become gardens where beautiful things are discovered.