This post began as a response to a recent conversation about service. My brother was becoming involved in various organizations, and over the course of discussing new service opportunities, certain predictable questions came up. How best to be of use? How to know? Where to begin? And, of course, how to sustain a life of service to others.*

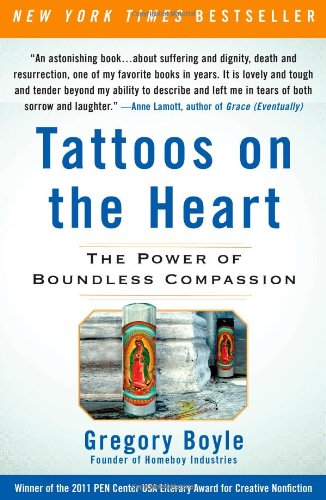

My thoughts turned immediately to Fr. Greg Boyle - specifically to an On Being interview with Krista Tippett that was my introduction to his tremendous presence, and to his book, Tattoos on the Heart, which I purchased immediately after hearing him speak. There are certain experiences about which, when remembered in certain contexts, with particular people, one is compelled to fervently say, "You must (see, hear, watch, try) this!" I did say this about Fr. Boyle's work, and about the interview, when it came up, but I was unsatisfied with my explanation as to why. I want to elaborate when recommending something and meaning it because - let's face it, most people don't have the time.

I'll start by explaining where I was when I heard the interview: driving home, Friday afternoon, about four years ago, sometime in early March. I was in my seventh year or so of teaching, which was long enough to have observed the way that, every year a certain strain of despair creeps in, bringing with it a particular line of questioning, which goes something like this: “What does it matter, what we do here?” I hear the question voiced as often among my closest colleagues as I do within myself.

My thoughts turned immediately to Fr. Greg Boyle - specifically to an On Being interview with Krista Tippett that was my introduction to his tremendous presence, and to his book, Tattoos on the Heart, which I purchased immediately after hearing him speak. There are certain experiences about which, when remembered in certain contexts, with particular people, one is compelled to fervently say, "You must (see, hear, watch, try) this!" I did say this about Fr. Boyle's work, and about the interview, when it came up, but I was unsatisfied with my explanation as to why. I want to elaborate when recommending something and meaning it because - let's face it, most people don't have the time.

In this post I will try to explain what is so affecting about the experience of hearing this man talk (via interview or in his book), in the hopes that whomever reads this may be curious enough to decide to listen and/or read for him or herself. I must make it clear at the outset that I am incapable of capturing his presence. This meager attempt to describe anything about it comes from believing that anyone who contemplates or acts on a desire to live all or part of ones life in service to others, must spend some time in the company of Fr. Greg Boyle, so I am compelled to try to explain why one may benefit profoundly from doing so.

I'll start by explaining where I was when I heard the interview: driving home, Friday afternoon, about four years ago, sometime in early March. I was in my seventh year or so of teaching, which was long enough to have observed the way that, every year a certain strain of despair creeps in, bringing with it a particular line of questioning, which goes something like this: “What does it matter, what we do here?” I hear the question voiced as often among my closest colleagues as I do within myself.

It was still several weeks away from spring break, but well enough into the year for it to have long been made clear that some sort of break, in a kinder world, would surely be manifest.

Maybe I chose to listen that afternoon out of some hope to learn something useful or edifying about how to better find a way to do what needed to be done - that is, to hang on. If so, it seems important to distinguish this impulse from my reasons for continuing to listen over the course of an hour’s drive. These can be explained more simply: because it is a sheer delight to hear this man talk. It is immediately clear that this is someone whose presence is so authentic and complex, so unassuming while at the same time so aspirational in its hopes of what human beings may be for one another, that it has the effect of making one feel cradled in the womb of a reality that one may have - for reasons relating to popular definitions of what is real and isn’t - ceased to believe in, at least completely. It is likely that if one encounters Fr. Boyle in such a state, one may be reminded back to oneself, in all of one’s childish hopes and dreams for what might be if people remembered one another in certain ways.

All I knew of Boyle, when I clicked Play to hear the podcast, was what I could see from the descriptor beneath the show’s title:

The Calling of Delight: Gangs, Service, and Kinship

A Jesuit priest famous for his gang intervention programs in Los Angeles, Fr. Greg Boyle makes winsome connections between service and delight, compassion and awe. He heads Homeboy Industries, which employs former gang members in a constellation of businesses. This is not work of helping, he says, but of finding kinship. The point of Christian service, as he lives it, is about “our common calling to delight in one another.” Listen here.

At the opening of this interview, Fr. Boyle announces, “I have this recurring nightmare that I am being interviewed by Krista Tippett and I am found to be shallow and lacking in faith.”

I am leaning in, now, and will remain so for the better part of an hour. As far as I can see, the only ones who can offer any useful instruction as to faith are the natural doubters. Although I may frequently admire those who seem ever sure of footing, I can never quite identify with anyone who seems immune to regular bouts of hearty self-questioning and a ripe colony of insecurities. I will always prefer the company of those who are willing to freely admit to questioning every step of the way, in an endless series of forward-leaning steps towards a place that is less a destination than it is a belief in what a destination might be if the world were other than it is, to anyone who claims to have figured out in any satisfactory fashion, a way of life so immune to puncture that he or she feels confident in selling it under the guise of a how to book. Tell me you know how its done and I’m inclined to call bullshit. Share your story as openly as you share your hopes in what might be and your doubts in what is being or has been done, and I will be your loyal listener forever.

Listening over the course of my drive home, I wish I could sit beside him at a pub at the end of a long day and buy him a beer. There are familiar tones in his doubts, and in those moments that are new and unfamiliar, any weary listener may be renewed to witness some some glimmer of what each of us is called to become, which is no more and no less someone with the sensitivity to better recognize the people one encounters on a daily basis, in order to better serve as someone capable of finding small moments in which to become the sort of mirror that has the effect of returning ones best self back to oneself.

I suspect that Fr. Boyle has this effect on many, which no doubt has much to do with his becoming a phenomenon, the man whom homies approach, as he recounts, to ask in lieu of, “Father may I have your blessing?”, “Hey G, Gimme a bless, Ya?” As I write this line it occurs to me that this is what each of us are asking for every day, some blessing from another. Some of us just ask more urgently than others.

A listener with any degree of formal experience in that area of human activity often called service cannot help but be reminded of the habit among so many of those purporting to “serve” of loving to recount how well they “helped” those they worked with. To anyone who has ever felt an inkling that there was something wrong with such a sentiment, know that Fr. Boyle is a longstanding leader of the tribe more inclined to listen than to preach, more inclined to serve in the sense of asking, “How may I help you?” as opposed to telling, “This is what you need.”

Tattoos on the Heart is not the sort of book you read because you want to know what happens next. It’s not a book to read in hopes of figuring out how the author “does it.” Its the kind you read because its written by someone you don’t want to stop being with. Boyles' God is an expansive creator, the divine presence that regardless of faith calls each individual to find the best of him or herself by coming outside of it.

In the Preface, Boyle describes his intentions for the stories contained within his book, around which he hopes to “slather enough thematic mortar [to] hold them together”:

"With any luck, they will lift us up so that we can see beyond the confines of the things that limit our view."

His intention, clear as it is from the beginning, does not fail to stun as it continues to emerge. As witness, one is forced to acknowledge that the thing preventing us from seeing the divine correlates almost precisely with the distance we hold between ourselves and others. Any careful witness of Boyle's testimony is forced to acknowledge that a full interpretation of "others," equates effectively with “those that we would prefer to dismiss.” One is forced to acknowledge a tendency to dismiss certain people who exasperate beyond a certain point. It is these, Boyle reminds himself as often as he does his readers, over and over again, who have the most to offer.

He cites the words of William Blake:

|

| Jacob's Ladder by William Blake |

“We are put on earth for a little space that we might learn to bear the beams of love,” and follows with the observation that “this is what we all have in common, gang member and non-gang member alike: we’re just trying to learn how to bear the beams of love.”

Boyle speaks often of being returned to himself in his work with “the homies,” and describes his own intentions as aimed towards returning others to themselves. He makes it clear, over and over again, that this is a cooperative process, one that cannot be achieved in isolation. He celebrates an open and inclusive sense of “church” to replace the “hermetically sealed” version that stresses keeping “the ‘good folks' in and the ‘bad folks’ out.” Boyle's God is no tight-lipped, vengeful judge, but an expansive, fun-loving and ever-patient source of opportunities.

Boyle meditates on this expansiveness often, observing that attaining it, paradoxically, tends to require a narrow focus, as “the gate that leads to life is not about restriction at all. It is about an entry into the expansive” which, as often as not, “comes to us disguised as ourselves.”

Through story, Father Greg reminds listeners how that which is sacred is found in moments of small humility and kindness. Boyle observes how in an effort to make the sacred more palatable, less difficult, “We’ve wrestled the cup out of Jesus' hand and we've replaced it with a chalice because who doesn't know that a chalice is more sacred than a cup, never mind that Jesus didn't use a chalice?” In his interview, Boyle offers a profound illustration of this sacrament, through a story related to him by one of the young men he had been working with.

(from the transcript of the interview)

A story I tell in the book about a homie who I saw sometime not long after Christmas Day. I said, "What'd you do on Christmas?" And he was an orphan and abandoned and abused by his parents and worked for me in our graffiti crew. I said, "What'd you do for Christmas?" "Oh, just right here." I said, "Alone?" And he said, "No, I invited six other guys from the graffiti crew who didn't had no place to go," he said, "and they were all …" He named them and they were enemies with each other.

I said, "What'd you do?" He goes, "You're not gonna believe it. I cooked a turkey." . I said, "Well, how'd you prepare the turkey?" He says, "Well, you know, ghetto style." I said, "No, I don't think I'm familiar with that recipe." He said, "Well, you rub it with a gang of butter and you squeeze two limones on it and you put salt and pepper, put it in the oven. Tasted proper," he said. I said, "Wow. What else did you have besides turkey?" "Well, that's it, just turkey. Yeah, the seven of us, we just sat in the kitchen staring at the oven waiting for the turkey to be done. Did I mention it tasted proper?" I said, "Yeah, you did."

So what could be more sacred than seven orphans, enemies, rivals, sitting in a kitchen waiting for a turkey to be done? Jesus doesn't lose any sleep that we will forget that the Eucharist is sacred. He is anxious that we might forget that it's ordinary, that it's a meal shared among friends. And that's the incarnation, I think.

The need for help is universal, and yet it is easy to forget, sometimes, how delivering the most essential aid, when it is most needed, often has much more to do with being that it does with doing. It's a matter of maintaining proximity and presence. There are times when, by focusing on why or how anything we "do" matters, we miss the point. There is no formula, no way to get it right, and as many of us know if we have ever been found in a moment of obvious need, and been confronted by someone who had an easy solution, the instinct to run from it is likely well advised. There are enough ideas out there. There are enough hows. When the time comes for fixing, anyone with enough hope, can figure out how or who to ask. Presence is harder to come by. Pain often involves a degree of desperation and despair, and yet, we are naturally resilient. All we need is someone to bear it with us.

One of the many striking moments is his observation that what is most worth seeking is this: “A compassion that can stand in awe at what the poor have to carry rather than stand in judgement at how they carry it.” Doing this requires standing with rather than apart. It involves doing what Boyle describes as “sharing our lives with those on the margins.” The effect of doing this is a profound widening of the circle that envelops the worthy, until none are left outside of it. The beatitudes (Blessed are the poor in spirit, etc, etc..) are not a spirituality, after all, he observes. Rather, "they are a geography," which as Boyle puts it, “tells us where to stand.” He reminds us that “in the monastic tradition, the highest form of sanctity is to live in hell and not lose hope.”

Trusting in Teilhard de Chardin’s vision of “the slow work of God,” Boyle stresses the importance of waiting in faith rather than focusing on results. “I’m not opposed to success,” he explains, “I just think we should accept it only as a by-product of our fidelity. If our primary concern is results, we will choose to work only with those who give us good ones.”

Instead of looking for satisfaction in results, Boyle chooses to delight in the community he serves. His wonder at the presence of the divine in those around him is genuine and contagious. The moments for laugh-out-loud recognition come often, as do moments of profound loss, as Boyle shares stories of the senseless deaths that emerge in a community where hopelessness fuels constant gang activity, as well as insights into navigating his faith in the face of such losses. Boyle holds his ground, standing at the edges, in kinship with "the easily despised and the readily left out," explaining his mission as such: "We stand with the demonized so that the demonizing will stop… we situate ourselves with the disposable so that the day will come when we stop throwing people away.” This only happens when we learn to delight and wonder at one another, in small acts of daily faith. Boyle reminds how service is less about grand-scale delivery of "help" and much more about learning to see oneself in others, to be returned to ourselves in doing so, and to grow our own capacity to return others to the sacred center of their own being - that which is most constant and most prone to being forgotten. You read the work of Fr. Greg Boyle, you listen to him speak, for the sheer delight that comes from remembering.

Instead of looking for satisfaction in results, Boyle chooses to delight in the community he serves. His wonder at the presence of the divine in those around him is genuine and contagious. The moments for laugh-out-loud recognition come often, as do moments of profound loss, as Boyle shares stories of the senseless deaths that emerge in a community where hopelessness fuels constant gang activity, as well as insights into navigating his faith in the face of such losses. Boyle holds his ground, standing at the edges, in kinship with "the easily despised and the readily left out," explaining his mission as such: "We stand with the demonized so that the demonizing will stop… we situate ourselves with the disposable so that the day will come when we stop throwing people away.” This only happens when we learn to delight and wonder at one another, in small acts of daily faith. Boyle reminds how service is less about grand-scale delivery of "help" and much more about learning to see oneself in others, to be returned to ourselves in doing so, and to grow our own capacity to return others to the sacred center of their own being - that which is most constant and most prone to being forgotten. You read the work of Fr. Greg Boyle, you listen to him speak, for the sheer delight that comes from remembering.

With That Moon Language

Admit something:

"Love me."

Of course you do not do this out loud;

Otherwise,

Someone would call the cops.

Still though, think about this,

This great pull in us

To connect.

Why not become the one

Who lives with a full moon in each eye

That is always saying,

With that sweet moon

Language,

What every other eye in this world

Is dying to

Hear.

- Hafiz

* This post is dedicated to my brother, Shane, who daily strives to model his behavior after the man he intends to be.

No comments:

Post a Comment