An Open Letter To Students in May of 2016

"Man is his own star; and the soul that can

Render an honest and a perfect man,

Commands all light, all influence, all fate;

Nothing to him falls early or too late.”

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by

And that has made all the difference.”

- Robert Frost

Now, as we prepare to close out our year, I’d like to revisit the question with which we opened it.

Prompt: Discuss how education and discipline make it possible for an individual to gain the freedom and power necessary to effectively shape identity.

Why now?

- Because it is the end of the year and I am feeling nostalgic about endings.

- Because I believe that endings, when properly honored, represent possibilities for growth and new beginnings

- Because I have a love for you that my daughter taught me, when she let me hold her in her arms and know her preciousness, who imbued upon me a deep desire to protect and preserve that which was most sacred and precious and in need of protecting.

- Because we are doing social justice research, and have been for… awhile. Against a backdrop of considering what it means to be an educated individual in a society that would encourage individual visions to surrender to the blind pull towards conformity.

- Because it is my hope that you may be able to think deeply about how you as an individual is in fact inseparable from larger forces at work within society.

So let’s talk about those forces against which I hope you will learn, as young warrior-scholars, to resist, defy, and ultimately defeat. I am speaking here of those powers that, in this day and age in America, work in a way that is counter to the ideals of democracy (freedom, liberty, equality, justice), which promote an agenda expressly designed for one reason and one reason only: to generate power. These are the forces of a market left unchecked by those untrained, unwilling, and discouraged from questioning that its motives may not be entirely human.

You are shaped by these forces before you are of an age to even question how they are shaping you, and yet possessed of a power that is a natural right of being human, to exercise agency to shape it. How do you know? Because you are trained to be consumers before you are trained to think for yourself. A good consumer consumes what is offered. A thinker asks, “Why are you giving me this?” and “Is it good for me?”

And a thinker with heart asks, “Is it good for others?”

And yet, you live in a time when you are being actively conditioned, by forces that do not have your best interest at heart, who wish to use your precious life force to feed their incessant need to get, acquire, possess: more money, more influence, more power, more control. Simply put, the more power these forces wield, the greater freedom they will have to control, possess, acquire.

I mean, do you ever wonder why we have so many zombie movies out there? Why zombies like the outrageously popular The Walking Dead, so capture our cultural imagination? The whole show is based on a ridiculous premise when you think about it: Picture the board room. Silence, then somebody offers, “Let’s make a show where a bunch of undead walk around terrorizing people, where the people who are not zombies have to camp out in fear and worry about being bit, all the while suspecting that some member of their camp has already been bitten and is thereby in the position of rendering every one of them into a permanent class of blood-thirsty, no-longer-human, walking dead.”

Apparently, the response went something like: “Cool. This is an idea whose time has come.”

Now I don’t need to be the one to remind you that there are a lot of ridiculous ideas out there. But what if - just for the sake of argument - the writers of this show were actually onto something? That the populace was actually primed to entertain the possibility that on some subconscious level, it had become entirely possible for the undead among us to threaten our very humanity and - what’s more - to turn us, in fear for our own safety, against one another?

What is really going on here? What is it about the overwhelming cultish popularity of this series that appeals to large masses of people, many of whom are (relatively) educated and sensitive individuals?

*[Disclaimer: I do not watch the show, as I do not watch most television series for reasons that are too complex to name here, but which may be oversimplified as: no cable, no interest, a strong aesthetic preference for books, and no desire to be subjected to the images of people being gored by zombies. I do however, follow television and other media trends via the analysis of philosopher, writers, and commentators, and friends whom I respect.]

Back to the question - could the answer possibly have something to do with the way that large numbers of people, despite living in an age where they may easily be living unwittingly as slaves to a machine that would gladly separate themselves from their own capacities for awareness and insight - have, somewhere, a small, sneaking, and yet persistent sense that the threat of the undead and ravenous blood-hungry hordes?

Listen, please. I implore you with a mother’s love for what you may be, the preciousness of which you have yet to begin to fathom: The fact that I wish to implore you not to take my statement at face value does not excuse me from needing to say it, because I know it is my conviction. I want you never to be killed by the forces that would wish to steal from you your life. I hope for you that you may never lose sight of your dignity, although you live in a society where the dominant forces conspire to take from you your life, who would train you to actually enjoy your own dehumanization, for whom you are at worst a casualty of war, and after that a prisoner, and after that a ward of the state, and after that a subject of surveillance, and - at the very least, a consumer. But never will they remind you or even allow you if they can help it, to recall your own dignity, that part of you capable of understanding - exactly what Emerson means when he reminds you, from almost two centuries ago, that it is within your very nature, and within the dream of democracy, and within every great religion that has ever held traction in the history of humankind, to remember how "The eye was placed where one ray should fall, that it might testify of that particular ray."

Testify.

Testify.

Testify: To what you know, and especially that which you have been trained to mistrust. Including me; do not trust me because I tell you that love you. Face it - I don’t even really know you beyond what I believe that I see. Just as you should never become so conditioned as to believe that you should trust any person who claims that they love you, who claims, by the sheer alluring whisper of words - to be capable of offering the source of your protection, relief, pleasure, and the need to be recognized for the unique individual that you are. In a culture that pays a lot of lip-service to honoring how “unique” and “amazing” you are, whose corporate greedy forces are actively at work convincing you that you “deserve” whatever ego-inspired, selfishly ignorant, materialistic, entitled shit you can imagine, and which would have you believe that the degree to which you “deserve” this - “fill in the blanks with any iteration of impulsively gratifying, satisfying need you can imagine” outweighs the force of civic responsibility that - if democracy exists at all - ties you to others in ways much more intricate, durable, and lasting than any infant’s untrained ideas of what matters most.

This is your final exam: Talk back.

No, forget that - shout back.

And forget the thing about the exam. This is the test of your life. Of our lives:

Shout back with the force of your being against the forces that would command you to silence. Take some time to reflect on the forces in your life that work to enslave you, and - to borrow a phrase from a fellow freedom-fighter, Bob Marley, “Emancipate yourself.”

If you can do it in a moment you can do it in a day.

Me+You=We

If you can free yourself in a day, you can free yourself in a week, a month, a year - a lifetime.

Me=You=We

If you can free yourself, even in a day, you can implore others - those would-be conformists, those fodders for the machine of perpetual greed, to free themselves, in much the same way that a single flame - no smaller than the light atop a 99-cent-store birthday candle - can be used to ignite the combustible surface of every other potential light it encounters. So find what it is that must be understood, and find a way to spread this message beyond yourself: Write, sing, blog, paint, rant. I don’t care how you do it, so long as you do this: get it out in a way that does the best you can do to allow others to hear, be affected, listen, and - most importantly - choose to act in response to what you share.

What do we share? We share questions and purpose. Like this:

Where is your flame? Where did you leave it? Who put it out? To which force(s) did you bow your head in acquiescence and say, "Okay, I surrender" - in spite of your stubborn best self - even though a few years or months or grade levels earlier, you would have shouted in their undead, blood-hungry faces, while you stood in defiance wearing a cape and your superman underoos and the leftover- chocolate mustache from your last indulgence because - to hell with decorum - you were alive and dying to fly and because of this you - if you were not killed before the moment when you learned to talk, shouted defiantly in the face of the dead lumbering zombie hordes that would oppress you and insisted, “I can fly!” I can Fly!” ”I can Fly!”

You were Superman once, too. And that’s why you loved him (You too, Wonder Woman.). Maybe that’s why you went to see him - along with a few million others any time within the last several months - take on Batman on the big screen. It didn’t really matter who you went to root for - the one who climbs walls or the one who played Clark Kent in one world and flew in another - the point was, you were willing to suspend your disbelief on some level - in the name of the divine wisdom that tells you that the capacity that lies inert within each of us is far beyond that which any of us habitually recognize.

Remember: You are being conditioned to forget this.

Remember:You are being conditioned to not ask questions.

Remember: people are natural conformists.

Remember the lesson of the Milgram experiment - You are trained to do what the experimenters tell you to do, despite how it may violate the essence of your very humanity:

Don’t ask.

Listen to the man in the white coat.

Don’t question.

Electrocute your fellow man to the point of death and feel like a good citizen, a model subject in the process.

And yet, remember this too: it was the ones who retained within themselves the ability to question and the agency to voice their own questions out loud - who saved countless innocent subjects from fatal electrocution. Who saved themselves from indoctrination into - except for a strong resistance movement - a class of undead, ruling zombies that have the power to exert a perennial reign of terror and social control.

Unless——-

Unless what?

The answer is for you to decide - not in a vacuum of engineered solipsism, but in harmony with other divine beings who are eager to sing, eager to ask, eager to be, laugh, dance, and celebrate.

Celebrate what?

That power within each of you, to change, by the very nature of

your awareness and your belief in individual agency and collective union - the nature of reality and the world in which you live.

How?

This, I cannot tell you.

You must determine this for yourself.

I can only remind you, in an effort to remind myself: Do It.

---

That’s my rant.

——No, not a rant. “Rant” is a word pandered by those who wish to marginalize the genuine voices of those speaking from the margins with conviction.

This is my song, my plea, my life’s sermon. It is possible that what I say to you now represents my singular gift, that testament to the particular ray on the particular branch within my particular line of vision, strengthened by my belief that it is the natural tendency and right of those around me to wish to sing in harmony and not discord.

This is my conviction.

Now, What is yours?

----

Shout back at me, rage, or hold your silence in a carefully contorted pose that you choose to relate in some way that defies my English-teacher bias on the towards the ineffable power of words.

As an English teacher, I believe in the power of words to communicate that which must be explained. As a writer, I understand better than most, the incredible weakness of words. I believe in working endlessly at the project of aiming to convey what my heart must express, and yet it has forever been my experience - and continues to be now - that words never come close.

Such is my lot; I am indeed a human being, subject to forces beyond my control.

And yet: I have power within me, and I believe it is my choice as a human being no greater and no less than any other being on this earth - now, and for as long as I choose to resist the forces that wish to convince me of my powerlessness - to shape, by the force of my convictions, the fabric of the reality in which I live.

So now I stand here before you - shouting, singing, dancing: even though my voice is broken and I can’t carry a tune that will necessarily be recognized as such; and even though I have only one arm and half a leg and I never seem to be listening to the same rhythm that everyone else is hearing. Even though my heart is broken.

The song I want to sing to you goes like this

“Hear this! Listen! Stop!”

and

“Change, like this… Here’s how...”

And the dance I have to offer is only this: one single outstretched hand and a leg that can’t keep from wanting to move. Even if the only how-to I have to offer for how is this: Let’s figure it out. Whatever it is, it’s bound to be better than this zombie food they’re trying to feed us.

You don’t have to be religious to believe in the power of communion.

This is what a human being can say for as long as he or she remembers their own power.

Against the battalions of zombies surrounding our ranks, shout with me:

Warlords and agents of destruction and greed, keep your drumbeat if it means that I must never break stride in order to keep up with it. If that’s the case I’m going to have to choose between believing in my own capacity for composing, and simply keeping up.

And say, or shout, or sing, or dance, or make signs, but anyway tell them this with all the conviction that should have - if they had their way - been trained out of you right now:

I can work my ass off to keep up, but if in the process I must surrender the music of my heart, I say to you, merchants of death, conductors of zombies - leave me behind.

I believe in music of the heart that breaks and bleeds and goes

on beating, and I believe that I am not alone.

Chorus of the human heart, voices of the voiceless who refuse to remain silent for eternity, rise up and speak.

Now is the time.

What will you do with it?

/ We

What do you know?

/ We

What will you do with what you know?

/ We

How will you use this knowledge to remind others in the chorus - how to be here?

/ We

Fly.

Go on, you beautiful beings.

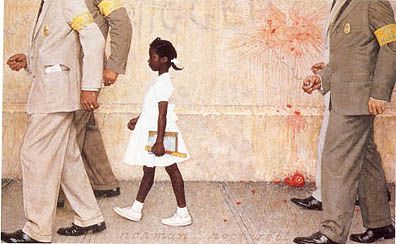

You are no earthbound clods. Your ancestors include Prometheus, and Moses, Siddhartha and MLK, Ruth, and Mary, and Spider Woman and the Sisters of Fate and the Sisters of Mercy, and Einstein and your baby sister before she could speak, and the child you once were before you were trained out of your greatest natural talents for being whole, and all of the prophets and geniuses of history who understood how to transcend their limited fates, and who acted, in spite of their training to the contrary - in response to this deep and profound understanding.

Fly.