For anyone who has ever longed, in the live-tweeting age of Instagram, snap chat, selfie sticks, reality-television housewives and lawsuits over the heat of freshly-brewed coffee, for a dose of something more serious and substantial, Alain de Botton is a good friend to know. I had the sense when I first picked up his The Consolations of Philosophy, a few weeks ago, that I had encountered the author before. My hunch was confirmed with a quick google search; it was a 2013 On Being interview with Krista Tippett, which I remember hearing at some pre-dawn hour during a Saturday morning run, in which he discussed his motivations for founding the School of Life in London, which he describes as a church for atheists. I was moved by the talk and by de Botton’s earnest search for truth and meaning beyond the world currently taken as “secular” while also resisting the dogmas of religion. His soulful sensibility and earnest searching is perhaps most efficiently conveyed by a survey of the titles of his books. These include, in addition to The Consolations of Philosophy: The Art of Travel, Status Anxiety, On Love (a novel), Essays in Love, The Architecture of Happiness, How Proust Can Change Your Life, The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work, Religion for Atheists: A Nonbeliever's Guide to The Uses of Religion, The News: A User’s Manual, How to Think More About Sex, A Week at the Airport, The Romantic Movement: Sex, Shopping, and The Novel, On Seeing and Noticing, and Art as Therapy: From the Collection of The National Gallery at Victoria.

In

The Consolations of Philosophy, Alain de Botton parses wisdom of the ages for everyday living, with searching questions and endearing wit. Let’s face it, a book that dares to attempt to distill wisdom of teachings of philosophers as diverse and wide ranging as Socrates, Epicurus, Seneca, Montaigne, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche - could easily become a litany of trite superficial distillations of profound truths. De Botton’s volume is fresh and meaningful because he is not trying to simplify the oeuvre of any of the characters in his enlightening discussion. Rather, he looks to them sincerely as wise elders, searching the teachings of each for clues that may help him to address a very specific and personal problem. His honesty is endearing, while affording the reader with a fresh lens by which to examine each thinker.

He reads with an eye for aiding and addressing particular human blights, and organizes his chapters around them, pairing each with a philosopher whose message offers complex varieties of consolation around the theme at hand. For “Unpopularity,” he turns to Socrates, for “Not Having Enough Money,” Epicurus, Seneca on “Frustrations,” Montaigne on “Inadequacy,” Schopenhauer for “A Broken Heart,” and finally, to Nietzsche for “Difficulties” in general.

De Botton begins by narrating his experience of being in “a deserted gallery on the upper level of the Metropolitan Museum of Art" on his way to find a container of his favorite chocolate milk before heading back home to London, and being struck by Jacques-Louis David’s 1786 painting, The Death of Socrates.

As he contemplates the work, de Botton observes how “the subject of which the Greek philosopher was the supreme symbol seemed to offer an invitation to take on a task at once profound and laughable: to become wise through philosophy.” The author elaborates with explanation of his desire to profile treasured insights of diverse philosophers across time:

|

| Jacques Louis David's The Death of Socrates |

In spite of vast differences between the many thinkers described as philosophers across time (people in actuality so diverse that had they been gathered together at a giant cocktail party, they would not only have had nothing to say to one another, but would most probably have come to blows after a few drinks), it seemed possible to discern a small group of men, separated by centuries, sharing a loose allegiance to a vision of philosophy suggested by the Greek etymology of the word - philo, love; sophia, wisdom - a group bound by common interest in saying a few consoling and practical things about the causes of our greatest griefs. It was to these men I would turn.

Also in the opening, he explains his rationale for desiring to cultivate philosophical habits of thought, supported by an illustration of two artifacts of pottery, side by side: one which could easily be found in a museum, the other which appears to have been sculpted by a distracted three-year-old with borderline ADHD who has possibly been sipping a bit too much of his grandfather’s scotch. In this vein, de Botton observes:

“Unfortunately, unlike in pottery, it is initially extremely hard to tell a good product of thought from a poor one.”

This strikes me as particularly applicable to the times at hand, which seem often to consist of a number of well-oiled and handsomely coiffed and manicured mouthpieces eager to spout off knee-jerk opinions in equally well-manicured rhetoric devoid of apparent flaw even if it is all bunk. For this, de Botton offers this explanation:

A bad thought delivered authoritatively, though without evidence of how it was put together, can for a time carry all the weight of a sound one. Bit we acquire a misplaced respect for others when we concentrate solely on their conclusions - which is why Socrates urged us to dwell on the logic they used to reach them.

Oh, Socrates. What debts we owe you, for showing, at expense of your life, how humans will predictably prefer doctrine and custom over truth, and how ignorance, when propagated efficiently en masse, tends to win, over and over again. You drank hemlock, and even the guards wept. Your wife, Xanthippe, had to be carried out over the scene she was making, but who could blame her? She was simply voicing what everyone felt. “This cannot happen! Look at this injustice! See it and be moved!” We see it, we are moved, but it exists anyway. We sigh, we drink, we look ahead in resignation. It can happen, and does, over and over again, world without end. Only the purest lambs among us can still weep in indignation. Still, there is comfort in knowing that this is how things are.

For daring to offer that happiness may be found in doing good (a position which placed him in stark opposition to Polos who argued that dictators were revered by masses), Socrates was tried by a biased jury and received the death sentence. In the last public argument of his life, he offered this:

If you put me to death you may not easily find anyone to take my place…

From the life of Socrates, de Botton offers “a way out of two powerful delusions: that we should always or never listen to the dictates of public opinion. To follow his example, we will best be rewarded if we strive instead to listen always to the dictates of reason."

For the chapter, “Consolation for Not Having Enough Money,” de Botton begins with “Happiness, an acquisition list,” which includes the trappings of great villas, impressive acquisitions, and - for the book lovers among us - “A library with a large desk, a fireplace, and a view onto a garden.” He then contrasts these with the ideas of happiness espoused by Epicurus - a thinker whom, until I read this volume, I mainly associated with justification for gluttony and orgies.

I have learned that I am not alone in this error. Epicurus, on the importance of sensual pleasure, is often misunderstood. He is widely known for observing how “pleasure is the beginning and the goal of the happy life” and he publicly confessed “his love of excellent food,” for, as he aptly observed, “the beginning and root of every good pleasure is the pleasure of the stomach. Even wisdom and culture must be referred to this.” And, perhaps one of my favorite observations, exemplary of de Botton’s keen sensibilities, how, “philosophy properly performed was nothing less than a guide to pleasure.” Here it becomes easy to see where interpretation of Epicurean thought veered into justification for a narcissism and gluttony that Epicurus himself never would have lived or endorsed.

So it is surprising (and refreshing in a food culture that is often over-hyped, overdone, and a bit too gourmet) to learn that for Epicurus, food was simple. As de Botton clarifies:

He drank water rather than wine,and was happy with a dinner of bread, vegetables, and a palmful of olives. ‘Send me a pot of cheese, so that I may have a feast whenever I like,’ he asked a friend. Such were the tastes of a man who had described pleasure as the purpose of life.

…He had not meant to deceive. His devotion to pleasure was far greater than even the orgy accusers could have imagined. It was just that after rational analysis, he had come to some striking conclusions about what actually made life pleasurable - and fortunately for those lacking a large income, it seemed tat the essential ingredients of pleasure, however elusive, were not very expensive.

De Botton goes onto carefully detail these: Friendship ("Before you eat or drink anything, consider carefully who you eat or drink with rather than what you eat or drink: for feeding without a friend is like the life of the lion or the wolf.”), Freedom (he and his friends bought a house together, grew their own vegetables, and lived on what would today be called a commune, where they shared responsibilities and lived simply), and Thought (chiefly for developing the ability to distinguish what is natural and necessary from that which is unnatural and unnecessary. It is precisely the lack of sufficient thought, de Botton observes, which is at the heart of so much of today’s unhappiness even in the face of relative material abundance. As de Botton notes, “our weak understanding of our needs is aggravated by what Epicurus termed the ‘idle opinions’ of those around us, which do not reflect the natural hierarchy of our needs…” while advertisers work to exploit our longing for forgotten needs (friendship, freedom) to tempt us towards desire for unnecessary things (fancy aperitif sounds good when the real craving is friendship, longing for a Jeep may be the manifestation of a desire for freedom).

|

| Peter-Paul Rubens' Seneca |

To address "Frustrations," deBotton looks to Seneca, opening with examination of the circumstances surrounding the philosopher’s death in Rome in April A.D. 65. Basically, the twenty-eight year old Emperor Nero had uncovered a conspiracy to unseat him from the throne, and was on a rampage executing (mainly by feeding to lions and crocodiles) anybody that he suspected to be in on it, including his half brother Britannicus, his mother Agrippa and wife, Octavia, a large number of senators, and eventually also his tutor, Seneca. The philosopher’s friends and followers were beside themselves with agonized grief and impotent rage at this injustice. Seneca reminded them here, to consider the logic of the situation (as provided via an account by Tacitus):

Where had their philosophy gone, he asked, and that resolution against impending misfortunes which they had encouraged in each other over so many years? ‘Surely nobody was unaware that Nero was cruel!’ he added. ‘After murdering his mother and brother, it only remained for him to kill his teacher and tutor.’

For de Botton, this account serves as an example of Seneca’s characteristic ability to meet “reality’s shocking demands” with well-honed stoic dignity, which he no doubt had opportunity to cultivate throughout a lifetime of bearing witness to such disasters as the earthquakes that shattered Pompeii, the burning of Rome and Lugdunum, the violent tyranny of Nero’s murderous reign, contraction of tuberculosis which sidelined his political aspirations, and subsequent onset of suicidal depression, and - as a result of a plot by the Empress Messalina which resulted in his disgrace - eight years of exile on the Island of Corsica. All of this, de Botton eloquently observes, afforded the philosopher “a comprehensive dictionary of frustration, his intellect a series of responses to [his experiences]” which result in a deep understanding of a critical truth: that “the sources of our satisfaction lie beyond our control and that the world does not reliably conform to our desires.” For Seneca, achievement of wisdom lies not in circumventing this (you can’t), but in “learning not to aggravate the world’s obstinacy through our own responses, through spasms of rage, self-pity, anxiety, bitterness, self-righteousness, and paranoia.” It reminds me of the best of realizations that I have sometimes read, from survivors of rape, cancer, abuse, and other traumas. At some point the would be victim changes the lens and the singular focus that would have relegated them forever to victim status- namely, the tendency to cry, “Why me?” - and the response becomes instead, “Why not me?” upon consideration of the large numbers of people facing similar ills. The knowledge seems to have the effect of removing the single greatest stumbling block to further progress, which is precisely the tendency to react by wallowing in any of the unwanted responses describe above. When you take away rage, self-pity, bitterness, and the like - what is left but to accept and move on? Yes, of course, there is the issue of anger, and much of this righteous, but what to do with it? Seneca observed, “There is no swifter way to insanity…” In his view, the primary cause of anger results from holding onto “dangerously optimistic notions about what the world and other people are like.” In short, “we will cease to be so angry once we cease to be so hopeful.”

As I write the line above, I can imagine, that if this post had more readers, surely some would be aghast at the notion. I’ve committed blasphemy by this acknowledgment that, after all, maybe it is true that even though anything is possible, everything is not. In an age of “Believe it, achieve it!” the notion of moderating one’s expectations may be a tough pill to swallow. Which is, one might observe in a vein of practicality, why it is called a pill and not something other, like a hot buttered crust of bread. We have to live here, and if we’re fortunate in the Epicurean sense, from time to time we’ll get to love the process. But, let’s face it, Seneca reminds, we don’t get to make up the rules of the game. “An animal,” Seneca observed, “struggling against the noose, tightens it… the only alleviation for overwhelming evils is to endure and bow to necessity.”

For "Consolation for Inadequacy," turn to Michel de Montaigne of the wooded hills in south-western France, circa the mid 1500s.

Montaigne observed “how far we were from the rational, serene creatures whom most of the ancient thinkers had taken us to be,” proposing that we were “for the most part hysterical and demented, gross and agitated souls beside whom animals were in many respect paragons of health and virtue - an unfortunate reality which philosophy was obliged to reflect, but rarely did: ‘Our life consists partly in madness, partly in wisdom…’”

From this he turns to a tender and personal reflection on the particular emotional and spiritual pitfalls of sexual inadequacy, and onto cultural inadequacy borne of the “speed and arrogance with which people seem to divide the world into two camps, the camp of the normal and that of the abnormal. Further still, to chart the waters of intellectual inadequacy, borne of certain “leading assumptions about what it takes to be a clever person” contrasting with the philosopher’s own personal distaste fore certain revered books which induced immediate bouts of deep sleep. He urged writing with simplicity, observing how there is “no legitimate reason why books in the humanities should be difficult or boring,” and reminded how such simplicity, naked of adornment, demanded courage, such as that exhibited by Socrates in his dirty cloak, speaking in his plain language, whose humble style is so easy to forget when presented in the sleek prose of his faithful student, Plato, for it seems, observes Montaigne, “we can appreciate no graces which are not pointed, inflated, and magnified by artifice… such graces as flow on under the name of naivety and simplicity readily go unseen by so course an insight as ours…” Simplemindedness may not be so bad, after all.

Onto the theme of "A Broken Heart," and the entrance of Arthur Schopenhauer, who seems, from an early age, born to despair. He had enough wealth that he did not have to work (though it must be noted that this was inherited only after his father’s suicide, which happened when the young Arthur was 17), he attended an English boarding school, and confessed to be preoccupied with mulling over human misery. When he finally relaxes, on a European tour following the completion of a masterpiece of a book,

The World as Will and Representation, which some critics take as explanation for the young man’s lack of friends- and attempts to entertain the company of a number of young ladies, he is categorically rejected by all. With few moments of reprieve, rejections by the objects of his affections becomes a running theme, and by his mid-forties he mainly keeps company with “a succession of poodles, who he feels have a gentleness and humility humans lack”. He appears to survive by maintenance of a strict routine: three hours of writing every morning, followed by flute-playing for an hour, after which he “dresses in white tie for lunch in the Englischer Hof on the Rossmarket” where he is described as “comically disgruntled, but harmless and good-naturedly gruff.” Despite the warnings of his mother that “it is not good” he regularly goes for months without leaving his room.

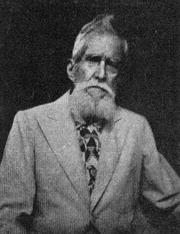

|

| Arthur Schopenhauer |

As he nears his sixties, Schopenhauer gains more attention from women and men alike, and his views towards women soften somewhat. Still, at the time of his death in 1860, at the age of seventy-two, he is firmly convinced that “human existence is a kind of error.”

De Botton observes how Schopenhauer’s particular brand of pessimism is may offer some useful consolation when it comes to matters of the heart, and the section he devotes to exploring how is particularly memorable.

As he puzzled over the peculiar pangs of love, Schopenhauer concluded that the lover is beset by a temporary insanity fueled by an instinctual pull to create the next generation. For this reason, one is pulled strongly towards a potential mate for reasons that often make no logical sense, and likewise, lukewarm or cool around people who are perfectly acceptable companions when the details of their persons are considered but for whom there is no particular spark.

As de Botton observes, this analysis “surely violates rational self-image, but at least it counters suggestions that romantic love is an avoidable departure from more serious tasks… by conceiving of love as biologically inevitable, Schopenhauer’s theory of the will invites us to adopt a more forgiving stance towards the eccentric behavior to which love so often makes us subject.”

The strange mystery of “Why him?” or “Why her?” is for Schopenhauer a matter of instinct. Namely, “we are not free to fall in love with everyone because we cannot produce healthy children with everyone… our will to life drives us towards people who will raise out chances of producing beautiful and intelligent offspring, and repulses us away from those who lower these same chances.”

The philosopher also concludes, bleakly, [in de Botton’s interpretation] that “the person who is highly suitable for our child is almost never (though we cannot realize it at the time because we have been blindfolded by the will-to-life) very suitable for us.”

To those who would offer exceptions to this rule, Schopenhauer would respond, “that convenience and passionate love should go hand in hand is the rarest stroke of good fortune.”

In short, as Schopenhauer regarded intense coupling, “The coming generation is provided for at the expense of the present.”

While many may no doubt find such views a bit severe, and perhaps colored by the author’s own ill-fate in love, it’s hard not to notice how they offer a sort of consolation in the vein of Seneca’s stoic acceptance, a reminder of how often human expectations for what will and should be are at odds with how they are.

"Consolation for Difficulties," featuring Nietzsche, brilliantly opens with this passage:

Few philosophers have thought highly of feeling wretched. A wise life has traditionally been associated with an attempt to reduce suffering: anxiety, despair, anger, self-contempt and heartache.

…

Then again, pointed out Friedrich Nietzsche, the majority of philosophers have always been ‘cabbage-heads.’

Nietzsche seems born for his particular brand of thinking, concluding relatively early in his scholarly life, influenced heavily by the work of Schopenhauer, that the greatest suffering is caused by pleasure-seeking; better to simply, through abstinence, aim to mitigate pain by embracing some measure of the inevitable discomfort of living. The goal here is obviously not enjoyment, but to preserve some measure of sanity which for Nietzsche is at odds with attempts to gain pleasure.

“the harder we try to enjoy [life], the more enslaved we are by it, and so we [should] discard the goods of life and practice abstinence.”

This is not to imply that the philosopher successfully followed his own advice consistently (his death results from an unfortunate case of syphilis most certainly contracted in a Cologne brothel). Periods of apparent simplicity and abstinence were frequently interrupted by violent pinnings for women who consistently rejected him - perhaps on account of the large mustache he wore, which appeared like the pelt of a small mammal, or perhaps because he was often painfully shy.

As his thinking developed, so did a deep understanding of the inextricable link between joy and pain, pleasure and displeasure.

What if pleasure and displeasure were so tied together that whoever wanted to have as much as possible of one must also have as much as possible of the other… you have the choice: either as little displeasure as possible, painlessness in brief… or as much displeasure as possible as the price for the growth of an abundance of subtle pleasures and joys that have rarely been relished yet? If you decide for the former and desire to diminish and lower the level of human pain, you also have to diminish and lower the level of their capacity for joy.

Very much a philosopher “of the mountains,” (for seven summers, he rented a cheap room in the mountains of southeastern Switzerland, which he felt to be “his real home.”) Nietzsche drew an analogy from his favorite surroundings to support his view on the duality of human experience:

When we behold those deeply-furrowed hollows in which glaciers have lain, we think it hardly possible that a time will come when a wooded, grassy valley, watered by streams, will spread itself out upon the same spot. So, it is, too, in the history of mankind: the most savage forces beat a path, and are mainly destructive; but their work was none-the-less necessary, in order that later a gentler civilization might raise its house. The frightful energies - those which are called evil - are the cyclopean architects and road makers of humanity.

His unfortunate death followed a state of rapidly debilitating madness that left him under care of his mother and sister. In reflecting on his work and those of his fellows across time and space, de Botton concludes with this potent truth, simple enough, but so difficult for human beings to fully understand:

“Not everything which makes us feel better is good for us. Not everything which hurts may be bad.”

Here’s a lesson for toddlers and five-year-olds (put the candy down, finish your broccoli, close your eyes even though you would dance and giggle all night), and yet even the most thoughtful among us may spend lifetimes learning what it really means.