In a column he penned in 2006, Canadian critic John Doyle of Canada’s Globe and Mail observed that “There are specific periods when satire is necessary. We’ve entered one of these times.” Suffice to say that post-2008 America, when Obama’s presidency corresponds ominously with a rash of media coverage (see Ferguson, St. Louis, Charlotte, and Queens) which may or may not be (but decidedly is) rooted in a nation’s dark history of racism, Doyle’s sentiment is perhaps as true as it ever was. Certain topics have become so marginalized or taboo in nature that any serious discussion of them is likely to be punished or ignored. In so-called “postracial” America, the preponderance of deeply-rooted racial inequality is perhaps one of the most concerning taboos observed in popular rhetoric. Despite glaring evidence to the contrary, the public discourse of Americans reflect a staunch determination to insist that race is no longer a valid axis of social inequality.

Enter Paul Beatty and his 2015 satirical masterpiece The Sellout, which has been hailed by Dwight Garner of The New York Time Book Review as “the best American satire of the millennium.” As a reader who was serendipitously introduced to Beatty in college, upon professor Bertram Ashe’s recommendation of Beatty's 1996 TheWhite Boy Shuffle, I expected, upon opening The Sellout, to experience a mixture of exhilaration and pain similar to what I felt when I first read his work; that is, exhilaration at being in the hands of a writer of such impressive virtuosity that the completion of a page is in itself a heady rush - and pain because the talents of this writer, as witnessed by one at the verge of an understanding that she may well be called towards writing as vocation - are enough to inspire complete surrender before one even begins. What’s the point? Beatty is that good. It takes only a few pages of The Sellout for any sensitive reader to understand that they are in the hands of a literary master of dazzling ambition who has arrived intent on delivering a walloping blow.

Talent, combined with drive and incisive focus on key issues of the day, make Beatty an ideal writer to address certain taboo subjects, and this reader early on considered it a boon to observe how, in The Sellout, Beatty pulls no punches. I can think of no one better to loudly suggest that the very idea of “postracial America” may be a farce, even given the fact of a Black president, and while this theme remains the critical focus, his scathing commentary doesn’t end there. Beatty hits hard, with precise blows, and his targets include the ceaseless “do-gooderism” of Dave Eggers along with the cloying presence of those whose overt and puritanical insistence on politically-correct language is especially offensive when ensconced in a comfortable buffer of bourgeoise accoutrements, and when it accompanies, in the name of liberation, a suspiciously instinctive readiness for filing out to march, “zombie-like” in procession at the next calling of any cause that seems remotely related to the mission of civil rights. He swings at the dirty conspiracy of gentrification (see below for more on this) and at the inherent reluctance of a nation of people quick to hang banners for Black History Month, to acknowledge certain of the most uncomfortable aspects of the struggle, especially those as represented by Hominy, an aging actor befriended by the protagonist, who is a former Little Rascals star whose fame has not only become the sort of thing that many people of all races would much prefer to forget about, also has the dubious distinction of being native to Dickens, an urban agrarian L.A. community that was once primarily black, which is now increasingly Mexican, in which the protagonist maintains one of the only working farms - raising satsuma oranges, distinctively luscious watermelon, fine strains of pot, and a few pigs, while riding his horse, as his father did, into and out of town - while the city itself is being silently wiped off the map by a conspiracy of real-estate interests who would prefer to pretend that it doesn’t exist.

I am getting ahead of myself here. The central situation of the story, as presented in the opening pages, is that the protagonist (last name Me, who is known alternately as "Bonbon" by his girlfriend, "Massa" by his slave, and "Sellout" by his nemesis) is on trial in the Supreme Court, for reinstating both slavery and segregation in his hometown of Dickens, an “urban agrarian" community in Los Angeles, where he is one of the last remaining farmers.

The protagonist is characterized largely by childhood of being raised by his father, a “social scientist of some renown,” who had left a position as a stable-hand in Kentucky to to become interim dean at Riverside Community College while establishing a small farm in LA. As described in one of the opening chapters:

As the founder and, to my knowledge, sole practitioner of the field of Liberation Psychology, he liked to walk around the house, aka “the Skinner box,” in a laboratory coat. Where I, his gangly, absentminded black lab rat was homeschooled in strict accordance with Piaget’s theory of natural development. I wasn’t fed; I was presented with lukewarm appetitive stimuli. I wasn’t punished; I was broken of my unconditioned reflexes. I wasn’t loved, but brought up in an atmosphere of calculated intimacy and intense levels of commitment.

…in his quest to unlock the keys to mental freedom, I was his Anna Freud… when he wasn’t teaching me how to ride [horses], he was replicating famous social science experiments with me as both the control and the experimental group.

Although his early service as lab rat has the unintended effect of making him decidedly indifferent about race, Me’s odyssey begins after the death of his father, who is essentially shot by police for driving while black. As he explains the circumstances that led him to become an agent of change in the community, Me explains his motivation as “a son’s simple wish to please his father.”

Me's father’s murder - which has obvious chilling echoes to national news headlines - is compounded by the erasure of his hometown of Dickens, which is described by an equally pernicious and relevant process that is the sort of familiar reality that generally flies under the radar of racist censure in ways that this passage effectively highlights, which make it emblematic of a new order of inequality that differs from its predecessor primarily in outward appearance while maintaining a de facto segregation that bears many of the essential elements that post racial America is so publicly proud of overcoming:

There was no loud sendoff. Dickens didn’t go out with a bang like Nagasaki, Sodom and Gomorrah, and my dad. It was quietly removed like those towns that vanished from maps of the Soviet Union during the Cold War, atomic accident by atomic accident. It was part of a blatant conspiracy by the surrounding, increasingly affluent, two-car garage communities to keep their property values up and blood pressures down. When the housing boom hit in the early part of the century, many moderate-income neighborhoods in Los Angeles county underwent real-estate makeovers. Once pleasant working-class neighborhoods became rife with fake tits and fake graduation and crime rates, hair and tree transplants, lipo- and cholosuctions In the wee hours of the night, after the community boards, homeowner associations, and real estate moguls banded together and coined descriptive names for nondescript neighborhoods, someone would bolt a large glittery Mediterranean-blue sign high up on a telephone pole. And when the fog lifted, the soon-to-be-gentrified blocks awoke to find out they lived in Crest View, La Cienga Heights, or Westdale. Even though there weren’t any topographical features like crests, views, heights, or dales to be found within then miles. Nowadays Angelenos who used to see themselves as denizens of the west, east, and south sides wage protracted battles over whether their two-bedroom, charming country cottages reside within the confines of Beverlywood or Beverlywood Adjacent.

…Signs that had read “Welcome to the City of Dickens” disappeared overnight.

As explained by Megan Le Boeuf, one of the hallmarks of satire is that “the main characters always feel they are doing something wrong by violating the rules and values imposed by society, when in fact they are acting morally, a fact obvious to the audience but not to them.”

In this vein, consider Beatty’s central character, driven to find a way to honor his father’s legacy, part of which involves his recognition throughout the community as the "whisperer" capable of talking people down from crisis situations, whose hallmark crisis-turning reminder to the desperate and despairing was, “You have to ask yourself two questions, Who am I? And how may I become myself?” The question becomes a compass for the odyssey that follows, and Me's unassuming approaches towards declaring some measure of freedom from existing axes of oppression, and to extend the same to those he cares about, lead him on a quest to bring back Dickens, which he does by replacing a “disappeared” freeway sign and painting drawing a white line around the former neighborhood, guided by an outdated map. His other offense, as slaveholder, is a role he takes only reluctantly out of respect for an elderly neighborhood icon, Hominy, to whom he feels indebted from childhood. Hominy, an interesting character in his own right, who, with his gentle nature, “minstrel smile,” and the way that he, like many child actors, he“never seem to age” is a symbol that speaks to the heart of Beatty’s critical offense.

Hominy’s very presence is the unsavory residue of a national past that no one wishes to acknowledge. A former child-actor, Hominy was a rising star on The Little Rascals series before it was cancelled at the dawn of the era that heralded a commitment to post-racial America - and with it, perhaps, a guilty or overly optimistic rush to believe prematurely in its existence. Hominy's tragic character is endlessly surprising and interesting in ways that can not be distilled into a single passage, but the essence of his predicament is that he, “like any other child star still standing in the klieg light afterglow of a long-ago cancelled career, was bat-shit crazy.” The pathos of Hominy’s fading fame is compounded by the fact that the few remaining loyal followers can not - as a result of the disappearance of Dickens - locate him in order to pay their respects. The compounding grief of his loss brings Hominy to a botched suicide attempt, at which point the protagonist muses on the particular poignance of his character:

If that naked old man crying in my lap had been born elsewhere, say Edinburgh, maybe he’d be knighted by now… But he had the misfortune of being born in Dickens, California, and in America Hominy is no source of pride: he’s a Living National Embarrassment. A mark of shame on the African-American legacy, something to be eradicated, stricken from the racial record, like the hambone, Amos n’ Andy, Dave Chapelle’s meltdown, and people who say “Valentime’s Day.”

When asked to explain his reason for attempting to kill himself, Hominy responds, “I just want to feel relevant.”

As part of his mental breakdown, Hominy becomes “unable to distinguish between himself and the corny ‘I owe you my life, I’ll be your slave’ trope,” he wakes the day after his failed suicide attempt calling his rescuer “massa” and begging to be whipped, despite the fervent protests of his reluctant slaveholder. When, mid-protest, the protagonist asks, “is there anything else that would make you happy?” Hominy responds, “Bring back Dickens.”

In an episode that I almost hesitate to relay in awareness that it may not translate well outside of the intricate context of the novel, the protagonists’s girlfriend Marpessa (a bus driver) - as a birthday present to Hominy arranged by "The Sellout," installs a tribute to the aging actor’s glory days in the form of a small placards reminding bus patrons of “Priority Seating for Seniors, Disabled, and Whites.” The satire really shines here - in part because of the predictable outrage that ensues from various patrons (When one man cries out, “I’m offended!” the narrator responds, “What does that mean, I’m offended? …It’s not even an emotion. What does being offended say about how you feel?”) and in equal part because of the absurdity of the situation, and finally because the real-life geographical and situational segregation is so acutely defined that Hominy is left eagerly waiting all day for a chance to give up his seat and would have gone completely disappointed except for the appearance of a redheaded Jewish beauty whose appearance turns out to have been arranged by the protagonist. In comparison to those of pre-Civil Rights America, today's buses may seem like democratic institutions, but the ride on Hominy’s birthday illustrates how its passengers are so notably non-white as to make any internal segregation within the system not only irrelevant, but redundant to boot.

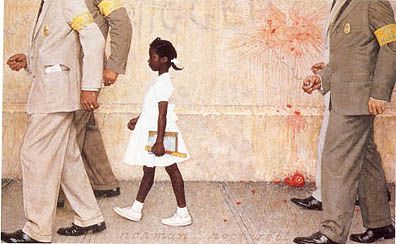

|

| Norman Rockwell's The Problem We All Live With |

In a serendipitous parallel, during the week that I was reading The Sellout, NPR’s This American Life aired the first of a scathing two-part program that effectively highlights some of the real repercussions of the American reluctance to directly address race. Entitled “The Problem We All Live With” (in homage to the iconic Norman Rockefeller painting of the same name), it is well worth the hour of listening, and far too rich to detail here except in the briefest of sketches as relates to the issues at hand. The episode follows the narration of Nicole Hannah, investigative reporter for The New York Times, in an documenting her well-earned (throughout decades of intensive research and personal experience on school reform measures, including integration) frustration over the refusal of most policymakers to discuss integration as a viable possibility, when research overwhelmingly supports integration as the single most (in fact, the only, Hannah argues) effective means of significantly reducing the achievement gap:

I'm so obsessed with this because we have this thing that we know works, that the data shows works, that we know is best for kids, and we will not talk about it. And it's not even on the table.

The program aims, as Beatty does, to address the unspeakable American problem of racial injustice so deeply entrenched that refusal to acknowledge race as an issue that continues to bear paramount relevance with regards to social and economic standing, and strongly illustrates how this deliberate glossing-over of legitimate concerns may arguably be rooted in some aversion to intricate complexity and nuance in an age and culture where the simple explanation is so often preferred, especially when ensconced in the alluring sheen of a national pledge towards “liberty and justice for all." Surely, by now, the thinking goes, such an ideal, now well into a the third century as an ideologies experiment, must be manifest. How eager we are to idealize, how slow to acknowledge our faults. This human tendency is magnified exponentially at the national level, especially when the veracity of a national creed is called into question by any truly sober examination of the national image in an unbiased mirror.

This brings me to highlight the final relevant talking point of this entry, which is by no means exhaustive of the fertile critical banquet that Beatty provides. It concerns precisely the issue of integration, and has the effect of complicating my impressions of the episode described above, Part 1 of which has the effect of leaving the listener with the message that “Integration is the answer, but we don’t consider it because we will not consider overt discussion of race.” Instead, the words used concern crime, security, funding, preservation of equity in real estate and and “the safety of our children.” (Listen to the podcast if you don’t believe me. At recordings taken from city hall meetings in 2013, when the closing of the Normandy unified school district, for failure to meet federal minimum standards threatened to allow thousands of students of predominantly black district to elect to attend high school in neighboring areas that, as the saying goes, “just happened to be” predominantly white, and you may find yourself wondering, as I did, if you are in fact listening to an eerily high-definition recording of a town hall meeting, circa the wake of the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision mandating recognition of the legal and moral illegitimacy of the “separate but equal” mentality that seems to continue to justify - in increasingly more complex nuances - the continued segregation of schools along racial lines, which most notably is the root of the reason that the term “achievement gap” continues to exist as a prominent phrase in national parlance on education, nearly half a century after it first was coined in recognition of certain uncomfortable truths that were obvious to any serious educator.)

Here’s the link to Beatty, which is precisely what landed him the hot-seat as defendant in a Supreme Court trial. To a principal of a local middle school and friend of his girlfriend, the protagonist develops and institutes a plan to segregate the local middle school, in opposition to the view that integration is a “cover up.” As he observes:

If you ask me, Chaff Middle School had already been segregated and re-segregated many times over, maybe not by color, but certainly by reading level and behavior problem… During Black History Month, my father used to watch the nightly television news of the Freedom buses burning, the dogs snarling and snapping, and say to me, “You can’t force integration, boy. The people who want to integrate will integrate.” I’ve never figured out to what extent, if at all, I agree or disagree with him, but its an observation that’s stayed with me. Made me realize that for many people integration is a finite concept. Here, in America, “integration” can be a cover-up. “I’m not racist. My prom date, second cousin, my president is black (or whatever).” The problem is that we don’t know whether integration is a natural or unnatural state. Is integration, forced or otherwise, social entropy or social order? No one’s ever defined the concept.

For many readers, including this one, Beatty’s sheer talent is enough to warrant effusive praise and devoted following, but what is even more interesting about The Sellout is what lingers long after the mind has steadied itself from the vertigo affected by Beatty’s sheer talent as a writer. It is his strength as a satirist in particular, that makes it so that certain themes, as attached to particular imagery and passages in the book, continue to occupy one’s thoughts during the spaces between readings and long into the time beyond the final page.