It was years ago when I first encountered a passing reference to this remark by Theodore Roosevelt: "It was my friend Verrill here, who really put the West Indies on the map." My curiosity was piqued and I wrote down the name. It seems anachronistic to think of knowing anyone who put any geographical place on the map. I figured that anyone who could simultaneously claim to have done so, while also being friends with the often larger-than-life seeming Theodore Roosevelt, must be worth reading about. I hoped he had perhaps a book or two that I might be able to hunt up on amazon.

As it turns out, A. Hyatt Verrill, in addition to his autobiography, Never a Dull Moment: The Autobiography of A. Hyatt Verrill, has authored 117 books and numerous works of short fiction and essays in the course of an illustrious career as zoologist, inventor, explorer, and artist. The volume and range of interests alone is a delight to marvel at, because it zoologist-inventor-explorer-artist-author sounds like the sort of job description that only could be described as a legitimate possibility by the most imaginative and ambitious of the ten-and-under set.

Of his life, Verrill observes, sometime around his seventieth birthday when he is penning his autobiography, "as I look back on the many years that have passed I can truthfully say that I have lived a full life and never known a dull moment." The remark sounds like the sort of familiar and forgivable hyperbole that is not uncommon among people inclined to look back on all or part of their lives with some degree of nostalgic gloss. In Verrill's case, the forward to his autobiography suggests that the statement may in fact be true.

This passage from the foreword of his autobiography may illustrate why:

Of his life, Verrill observes, sometime around his seventieth birthday when he is penning his autobiography, "as I look back on the many years that have passed I can truthfully say that I have lived a full life and never known a dull moment." The remark sounds like the sort of familiar and forgivable hyperbole that is not uncommon among people inclined to look back on all or part of their lives with some degree of nostalgic gloss. In Verrill's case, the forward to his autobiography suggests that the statement may in fact be true.

This passage from the foreword of his autobiography may illustrate why:

Verrill has discovered and described more than thirty new species of birds, reptiles, shells, and insects. He was the first man to discover a process of natural photography and the first to photograph marine invertebrates, and insects.

He re-discivered the almost mythical Solenodon paradoxus in the Dominican republic. He was in charge of an expedition that partially salvaged a Spanish galleon sunk in the West Indies in 1637. He discovered and excavated the remains of a previously unknown pre-historic culture in Panama and has excavated countless tombs and ruins in South America and has lived among more than one-hundred Indian tribes in South, Central, and North America.

He has made ninety-nine trips to the West Indies and Latin America, has crossed the Atlantic eleven times, and has devoted nearly forty years to jungle and desert explorations in Central and South America.

He has built boats, voyaged on a square-rigger to the West Indies, cruised through the Antilles on a vessel once a pirate ship, has served as steward, assistant engineer and purser on West Indian cruise ships and has held a Master's Certificate.

At one time he was a member of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show and as an expert rifle shot, demonstrated ammunition for the Winchester Arms Company...

He has discovered and patented a refining process for sulphur and at one time developed and worked copper and gold mines in Panama. He has collected thousands of archaeological and ethnological specimens for the Museum of the American Indian, New York City, and made a series of over one-hundred oil paintings from life of South and Central American Indians...

It goes on, but the passage above fairly gives a taste of a life that may indeed have verifiably been without a dull moment, lived from the years 1871 to 1954. Son of prominent zoologist Addison Emery Verrill, one might say he inherited the family business. One might also say that a certain amount of wealth certainly played a role in sponsoring the explorer's life and enough leisure time to spend documenting his perceptions of the world. Both observations would be accurate, no doubt, but neither would be sufficient to account for the vast range of interests and the intense, careful, and lively attentions given to each over the course of his astounding life. Its a life that amazes on two key fronts: one concerns the scope, volume, and quality of work; and the other, the way that it represents a sensibility particular to someone who came of age at a particular era, situated at a pivotal crossroads when scientific advancements and burgeoning discoveries could be embraced without the postwar disillusionment and angst that would color the sensibilities of later explorers.

Strange Birds is one volume in a series of "Strange" books, including Strange Animals and Their Stories, Strange Creatures of the Sea, Strange Customs, Manners, and Beliefs, Strange Fish and Their Stories, Strange Insects, Strange Prehistoric Animals, Strange Reptiles, and Strange Sea Shells.

Verrill's life presents a brimming testimony to the power of the seeker, who never seems to abandon a child-like delight in the new worlds he encounters. Consider, for example, some of the titles and subtitles in Strange Birds:

|

| One of Verrill's creatively-captioned illustrations |

My selection of Strange Birds came about because: 1) I was imagining a character in a story who had an unusual interaction with a bird of unusual personality, and thought the book might offer insights (it did) and 2) It is one of only a handful of volumes available at a reasonable (sub $15) price on amazon. Many are out of print and the price reflects this, often upwards of $50. I have no doubt such would be money well spent, considering the richness of this volume, but the higher priced volumes are not, for the time being, in this teacher's budget. What is most fascinating about Strange Birds - as, I assume perhaps about each volume in Verrill's considerable oevre is glimpse into the hunger of the mind, the eager strain that wishes to map the world, the type of sensibility that is capable of sustaining a narrow focus on a particular aspect of the vast wonders of the world, and holding it for as long as necessary to uncover certain mysteries that are inaccessible to the more casual observer. The best among the living often seem to be those who can find some narrow opening into an extraordinary world and willingly submerge themselves in it at great depths. Verrill's work represents a life of such practice, where the sustained focused is serially shifted only after each prolonged period of study. His list of published books includes volumes on such diverse interests as knot tying, deep sea hunting, native edibles, gardening, automobile operation, lost treasures, pirate love stories, "Pets for Pleasure and Profit," perfumes, radio detectives, smuggling, geology, paleontology, and a wide range of interests in particular fauna, flora, geographic regions, and civilizations. A skeptic might accurately observe that volume of work is measure only of capacity for production, and says nothing in and of itself of talent. With this in mind, it may come as great relief to the skeptical new reader of Verrill’s work to find that he is truly a top-notch writer. One feels while reading that one has gained access to a world that is no longer accessible in precisely the same way, in an age of constant distraction by complex demands. Close examination of any detail of life, by anyone other than the officially recognized specialist, is arguably as important now as it ever was, but in the modern age, it can sometimes seem like a lost art.

- How birds play hide and seek

- Gaudy cousins of the crow (on birds and interior design)

- Strange birds and their nests

- Bird pugilists

- Birds with four feet

- Bower birds and decorating (featuring a tame crow named Dom Pedro and a blue jay named Sampson)

- The bird who shaves

Or, this passage on Dom Pedro, the infant baby crow of insatiable appetite:

“How many times a day I fed that baby crow I would hesitate to state, but there are limits to even a foster parent’s patience and perseverance, and very soon I decided that it was a case for stern discipline and that my infant prodigy must be brought up to observe regular meal hours.”

This writer's confidence in his ability to accurately assess the lay of the land, and the characters of the creatures he finds within it, is something that seems almost quaint now. I do not mean to dismiss it as such, but there is no separating the man (as scientist, writer, explorer, or otherwise) from the time in which he lived, even when his work demonstrates timeless appeal. One cannot help but notice the childlike wonder evident in this life's work, including titles reflective of such a vast array of interests. Its difficult for a modern reader not to wonder how someone could be so authentically motivated by a desire to map the world, while appearing to maintain an unflagging belief in his ability to do, given enough time. Where is the angst? Where is the doubt that what one sees is really what is? Or the existential uncertainty verging on despair that come from contemplation of all that is yet unknown? If there is evidence of any of these characteristically modern sensibilities to be found in Verrill, I have yet to notice.

These thoughts are perhaps influenced by the fact that I have recently read Susan Sontag's 1965 essay "One Culture and the New Sensibility" in which she contemplates profound shifts in consciousness of the modern era, which call for the emergence of new artistic sensibilities in order to convey new ways of seeing. She cites these views of inventor Buckminister Fuller, who observes how:

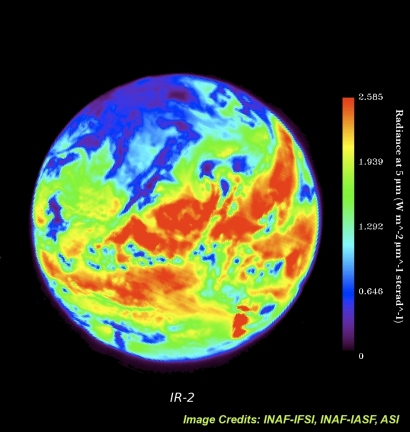

The Earth in infrared In World War I, industry suddenly went from the visible to the invisible base, from the track to the trackless, from the wire to the wireless, from visible structuring to invisible structuring in alloys. The big thing about World War I is that man went off the sensorial spectrum forever as the prime criterion of accrediting innovations ...All major advances since World War I have been in the infra and the ultrasensorial frequencies of the electromagnetic spectrum. All the important technical affairs of men today are invisible ... The old masters, who were sensorialists, have unleashed a Pandora's box of non-sensorially controllable phenomena, which they had avoided accrediting up to that time ... Suddenly they lost their true mastery, because from then on they didn't personally understand what was going on. If you don't understand you cannot master ... Since World War I, the old masters have been extinct...

For Verrill, it seems that his discoveries and documentation of the unknown world are always fresh and always also in the realm of that which is believed to lend itself - given enough time - to being efficiently charted, documented, mapped, and presented under the title of "The Boy's Book of..." (for Verrill, the "Boy's Book" volumes include guides on carpentry, whalers, buccaneers, outdoor vacations, and collecting for young naturalists, to name a few). One wonders how long we exist as a society until we see the title "The Boy's Book of Quantum Physics" or "The Boy's Book of Privacy Protection in the Age of the CyberHack", "The Boy's Guide to Selecting and Preparing an Ethically Raised and Sustainably Source Piece of Meat," or "The Boy's Guide to Apocalyptic Preparedness." Different times call for different titles, and the age when one may present in all seriousness, a guide to knot tying and/ or bird-naming seems to have come and gone. It raises the question, "What has replaced this age?" I think that one reason that I am so fascinated by the world of A. Hyatt Verrill is that I simply do not know.

If this strain seems cynical, let me attest to my continued amazement at those who continue to discover uncharted territories in the supposedly known world of creatures above the cellular level. I half-suppress a giddy giggle while reading a recent New Yorker story on how an entomologist in LA (Brian Brown), after betting a friend that he could discover a new species practically anywhere, recently spent a year pitching tents in LA backyards, and subsequently discovering and naming no fewer than thirty new species of insect life. Or the work of explorer and photographer Susan Middleton's who recently released Spineless, a stunning volume of full-color photographs of marine invertebrates, presented with a detail and artistry never before conveyed upon such species, using a technique she developed herself. I may look longingly at simpler times, those that allowed for the development of a man such as A. Hyatt Verrill, but I would like to believe that I live at a time most conducive to the particular sensibilities that I am most highly suited to: a unified and simultaneous awe for the known and the unknowable, a desire to wrap my arms around the world that I am called to document, verging on despair that this will never, in this lifetime, be done, and morphing once again into unrelenting awe at the remarkable strain of inherited humanity that insures me that there is something worthwhile in trying anyway. Here's to the endless exploration of all that is unknown, and to awe at the sheer depths of our shared incapacities for properly naming it, and to those perennial human inadequacies in the face of the divine that leave wonderers everywhere looking up with tingling scalps and goosebumps, whenever the night is clear enough to tempt the avid seeker to try to take it all in.

No comments:

Post a Comment